What's wrong with the Climate Change Act?

Or, how the real Deep State holds back decarbonisation and growth by accident

The UK’s former Prime Minister Liz Truss has penned a column that claims that Britain is in the grip of a “Net Zero Elite”. She argues that these secretive members of the Deep State have forced Britain down a path of permanently higher costs and permanently lower growth, and that the only pathway out of this is to revoke the Climate Change Act in favour of what she describes as a ‘Climate Freedom Act’.

One could rather uncharitably feel that this is an enormous boost to that self-same elite, inasmuch as Truss has personally demolished the case for her preferred low tax low regulation state for at least a generation. After all, asking to be free of the climate is tantamount to demanding that Britain relocates to Mars, taking the logic of Brexit to an extreme degree.

Figure 1: London under a second Truss Premiership

But to dismiss this argument would effectively avoid a debate that Britain needs to have as we enter into a period of higher interest rates that will push up the cost of decarbonisation. Leaving the case for managing the cost of Net Zero to the sceptics runs the risk of creating a political fissure that is about whether we decarbonise or not, rather than how we do it. And there is a debate to be had.

Truss’s charge is that decarbonisation will hinder growth. In thinking this, she is in disagreement with the overwhelming majority of the public (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Agreement with statement, “Tackling climate change will be good for the economy”

Source: Stonehaven Compass Poll

The public is joined in this attitude by the Climate Change Committee, the independent body charged with reviewing the Government’s climate change policies. They commissioned research alongside their work on the Sixth Carbon Budget setting out an expectation that the UK’s economy could grow by an extra 2-3% up to 2050 if we deliver Net Zero compared to not doing that. This is principally driven by three factors:

- Higher investment in more capital-intensive technologies enables us to utilise spare capacity in the form of otherwise idle capital and the unemployed;

- Lower spending on imports of oil and gas keeps more money in the UK and therefore implicitly increases spending;

- Dynamic innovation, especially in renewable generation, lowers power production costs down below their current long-run average and therefore reduces input costs to the economy.

The modelling that underpinned this research has been heavily criticised on grounds of non-orthodoxy, and there are very important questions about whether there genuinely is spare capacity in the UK’s economy, especially in the context of higher interest rates.

A more reasonable position would be to take the number recently published by the Energy Systems Catapult of a total cost of Net Zero being around 1% of GDP; to put it another way, this implies that our economy in 2050 will be about 1% smaller than it otherwise would’ve been if we hadn’t sought to decarbonise. It is reasonable to spend 1% of GDP to avoid a potential downside cost of between 5-20% of GDP by 2050, but it is clearly a cost. It is therefore reasonable to ask whether the structures put in place by the Climate Change Act are delivering decarbonisation in a way that maximises growth.

Structures, not Sectors

In doing so, I don’t want to fall down the rabbit hole of arguing whether a specific technological solution is good for growth or not. Too much of the debate in this space wears the clothes of growth – lots of use of ‘investment’, ‘jobs’, ‘infrastructure’ – without a plausible theory of how a particular technology does in fact improve productivity or allocate capital more efficiently. Capital we spend on decarbonisation is capital that could otherwise have been spent on more productive but higher carbon uses. While this is increasingly untrue in particular areas, pace the CCC work above, highly skilled people who work on low carbon tech could often deliver higher value if they were employed elsewhere. Oil and gas companies normally pay more for the same skillset than renewables companies, in part owing to the Soul Tax the former imposes on their employees, but also because they can make more money out of those skills. People taking lower paid jobs rather than higher paid jobs lowers productivity.

Decarbonisation therefore has an opportunity cost and ensuring that this cost is minimised – and indeed turned negative – should be a key aim of our institutional structures. There is a useful debate to be had in this space, which takes in levels of spending, how the UK organises its decarbonisation efforts, and how the Civil Service discharges them.

The UK’s decarbonisation framework is laid out in the Climate Change Act. Our progress towards a 2050 target of any scale is to be delivered under a framework of carbon budgets; five-yearly intervals with a specific volume of emissions allocated to each. The relevant Secretary of State of whatever the climate change department is called today must “prepare such proposals and policies as the Secretary of State considers will enable the carbon budgets that have been set under this Act to be met.” These ‘proposals and policies’ are laid before Parliament in the form of a Carbon Plan.

To draw back the veil on how this process works, a Carbon Plan is prepared by a central team within the climate Department and submitted to the Secretary of State for review and approval. This is a months-long process involving commissioning work from specialist teams within the Department and from other Departments that are relevant for climate action, such as the Department for Transport. All this information is fed into the Secretary of State through written advice, regular meetings with Special Advisors and, ultimately, preparing a lengthy document for them to review and approve. All of this is in the service of ensuring that the ‘considers’ test above can be met.

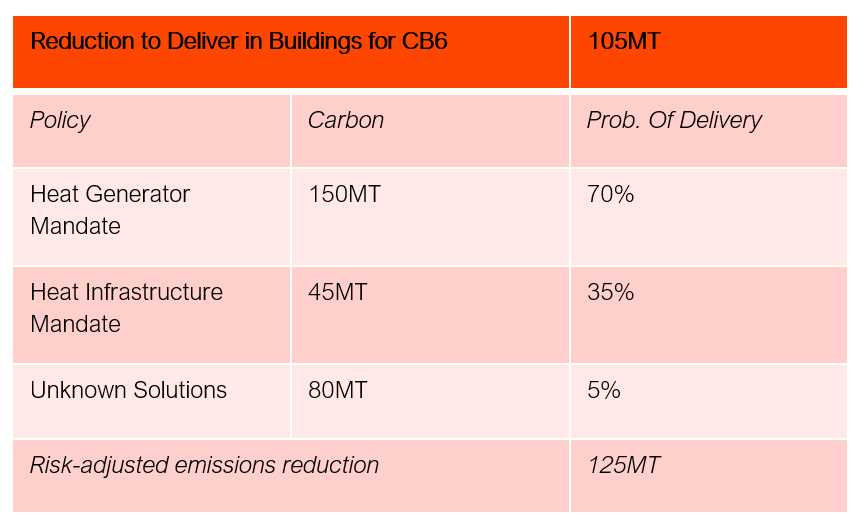

The word ‘considers’ is therefore doing a lot of work; what it means is that the Secretary of State must have the reasonable belief that their policies will deliver their carbon budget. It is precisely this test that has seen multiple Carbon Plans subject to judicial review; NGOs have asked the courts whether the Secretary of State had enough evidence to have a reasonable belief their plan would deliver (the 2022 case) or whether the plan as stated had an adequate evaluation of the actual risk attached to the policies involved (the 2023 case). This means that the pressure on that central team to deliver something legally robust is intense, and this cascades down through the Department to specialist teams. Those teams are sent forms that effectively ask, “What’s the thing you’re proposing, what number of bits of kit will it deliver and when, and what number of megatonnes of carbon do you expect to save?” You can see the outputs of this process throughout the most recent carbon plan (Figure 2).

Figure 3: Heat & Buildings section of 2023 Carbon Delivery Plan

What should be immediately obvious is that this process almost incidentally tells against some of the factors the CCC’s commissioned report regards as vital for delivering growth, especially ‘dynamic innovation’. The above table is based on a particular characterisation of particular types of technology where enough is known to be able to reasonably state that if delivered at X scale they will deliver Y emissions reduction. In the pursuit of delivering a reasonable belief, the Government inevitably picks winners, and therefore finds itself centrally planning much of the economy. This is not conducive to growth.

Many of my pro-climate-action friends might be happy with this trade-off; it is not unreasonable to accept slower growth in service of keeping the planet habitable. And indeed, I would have sympathy with this argument if Government was actually any good at central planning. For many of the technologies required for decarbonisation too little is known to make claims about their performance or deliverability, and many of the Government’s Carbon Plans that include them for the purposes of compliance are based on remarkably shonky analysis. As an example, observe Figure 3.

Figure 4: 2013 projected installations of low carbon heat technologies

Source: Renewable Heat Incentive Impact Assessment 2013. ASHP = Air Source Heat Pump. GSHP = Ground Source Heat Pump

You will observe that the 2013 projected number of heat pumps deployed by 2021 was two thirds higher than the number actually existing in the 2023 plan. The failure of the Renewable Heat Incentive scheme to deliver is one of the little-covered tragedies of UK decarbonisation policy but is indicative of the risk to decarbonisation of relying on this kind of technology deployment-centric approach.

One could even make the ‘reasonable’ argument that relying on such projections as evidence of delivery is in itself unreasonable; this, interestingly, is the case being put forward by Client Earth as part of its suit against the 2023 Carbon Plan. This case by itself will change the incentives on the climate Department, but in my view we need to go further for a genuinely pro-growth climate framework.

In doing so, we should look to learn from the past. The UK has tried centrally planning energy before, during the period in which energy was nationalised after the second world war up till the end of the 1980s. The Central Electricity Generation Board, the body responsible for planning and administering the electricity system, almost inevitably over-procured capacity and passed that cost onto the consumers it served:

“Manifestly, the national planners have consistently got it wrong about the capacity required for generation in this country… in the last several years there has been great over-capacity as the result of centralised planning… central planners make big mistakes.” Michael Spicer MP, House of Commons Standing Committee E, February 21st 1989

Decision, not default

It is important to emphasise that the process above has arisen not through any particular decision made by any particular Minister or indeed official, but rather has been the output of dozens of smaller choices made by many people over the years since the Act was passed. In part, this represents a lack of curiosity from Ministers as to how the sausage is made; they ask for advice on what should be in their Carbon Plan, but rarely ask how those options are developed. And while more thoughtful officials do occasionally buck against this process in order to deliver more interesting options, the grind of the process and the sheer lack of resource inside the Department tells against such minor acts of rebellion.

This means that the UK has decided to run its most economically important commitment through a centralised planning process not through design, but by default. Indeed, the Government has spent much of the last decade banging on about the virtues of the market while accidentally taking myriad decisions that strip its virtues out of the energy system. Since the passage of the Act, the UK has had 11 Secretaries of State responsible for its delivery, all of whom have just about managed to get to grips with the difference between electricity and energy before they are whisked away to the backbenches, another portfolio, or to face criminal charges. None of these individuals have been presented with the choice of, “Do you want to centrally plan decarbonisation y/n.” And yet, here we are.

What is needed is not another round of exhausted officials coming up with ideas to satisfy the last few megatonnes of Carbon Budget 7, but rather a wholesale rethink of the way in which plans are developed and designed, one which prioritises producing low carbon products people actually want to buy and utilises information distributed around the country rather than that clumped in Whitehall. One which is pro-growth, and in being so represents the best chance of ensuring long-term buy-in to decarbonisation.

Risk, not fake certainty

What would such an approach involve? Firstly, incentives matter, and they matter just as much in bureaucracy as they do in markets. All the incentives within the climate department for delivery are structured around producing policies that target technologies. The most successful policy in terms of cutting costs and thereby delivering growth, Contracts for Difference, was an almost accidental output of an instruction to deliver a set number of gigawatt-scale nuclear plants. Your career as an official does not benefit if your response to the central carbon plan team is, “Actually, we don’t know which tech is best, so we’re going to implement a carbon tax. No, we can’t tell you what it will deliver, because we don’t have enough information about how technologies and consumers will respond to market forces.” The UK does in fact have several overlapping carbon taxes, including the UK Emissions Trading Scheme, the Climate Change Levy, Fuel Duty and the Carbon Price Floor, the benefits of which have to be calculated very carefully to avoid double-counting the benefits of policies implemented in the same sectors the taxes cover. Our hypothetical official above really exists but is required to pretend they know more than they can possibly know in order to advance their career.

If we want to untangle this mess of poor incentives, centralised planning and inaccurate projections, we need to rethink how officials are rewarded and how carbon plans are structured. The Climate Change Act is actually helpful in this regard; the ‘confidence’ test is highly flexible and can be delivered through a range of decarbonisation frameworks.

Officials in specialist teams need to be rewarded for overdelivery against stated emissions savings. The idea of this is to incentivise the development of policies that have the potential to wildly outperform, much as Contracts for Difference auctions did until they were crippled by Government attempting to set prices.

Overdelivery can be achieved in a number of ways: through technology being more effective than initially thought, through it being cheaper than initially thought, or through the public buying more of it than expected. Crucially, none of these things are predictable or controllable from Whitehall; instead, officials will need to generate dynamics that compel businesses to focus on cutting costs, improving technology and selling to customers, otherwise known as markets. And these markets will need to bite hard; one of the issues with the aforementioned RHI is the extent to which small businesses selling heat pumps could happily trundle along making a reasonable living supplying a relatively small market at a fixed price. Businesses need to be subject to risk.

Given there would be an element of luck involved, to manage the risk of officials becoming high rollers with taxpayers’ cash, officials would be rewarded for winning high risk gambles but also for accurately assessing the probability of delivery. This means that for a given submission to a carbon plan, an official involved in its preparation would be rewarded in proportion to the extent to which it overachieved against its projected emissions savings or for the extent to which those savings were accurately projected. Officials that preside over policies that fail to deliver get only their basic package.

As a result a chunk of a civil servant’s salary will be several years in arrears, which will create new incentives for civil servants to stay in a particular policy area to ensure delivery is achieved. This is analogous to how share options work in the private sector and creates stronger incentives to devise policies that rely on innovation to deliver oversized outcomes - rather than rolling forward current technologies at a fixed cost.

To create a framework that is welcoming of these kinds of measures, Carbon Plans should be restructured to Carbon Portfolios; an explicit range of bets that Government has placed in the form of policies with a carefully evaluated probability of delivery attached. An illustration of this is provided in Figure 4.

Figure 5: Illustrative ‘Carbon Portfolio’ table

This approach creates the space for innovation by enabling Government to explicitly make market risk part of its core strategy, and by steering away from mandatory technology deployment policies. It is this which creates the dynamism that delivers growth. It is also likely more legally robust than the current route. Existing plans assume 100% success in delivery, which is currently only acceptable because judges feel unable to dispute the advice provided by officials to Ministers; this is not something that will always be true.

Deep thought, not deep state

What I have outlined above is a summary of the real ‘deep state’ so loathed by our least successful Prime Minister: officials working within structures that compel particular kinds of policies to be brought forward without anyone ever actually making a positive choice to put those structures in place. There is no Net Zero elite; merely people trying to do their best in a system where no-one is really in charge because Ministers don’t hang around long enough to fully diagnose why they can’t implement the market-friendly policies they say they want.

That being said, there are areas where officials could look to improve without Ministers having to understand the complex structures of the modern state. A greater sense of humility in the face of technological uncertainty is necessary across Government if decarbonisation is to be delivered cheaply. There are far too many cases in which Government or an independent regulator is seeking to make choices it believes are in consumers’ best interests without allowing actual consumer preference to be taken into account.

For example, the Clean Heat Market Mechanism – by far one of the more progressive policies in the Government’s armoury inasmuch as it leaves part of the job of understanding what consumers want to the people who actually talk to them – still involves picking winners. The policy requires heating system suppliers to supply a certain number of low carbon heating systems to customers, a number increasing every year. But what counts as a low carbon heating system is carefully constrained to not just heat pumps, but particular types of heat pumps. This is driven by officials being concerned about consumers making the ‘wrong’ choice for reasons exogenous to the heating device itself; rejecting air to air heat pumps because some models of them use climate unfriendly F-gases, for example. The logical conclusion that that these exogenous factors should be subject to separate policy rather than trying to do everything through a single instrument is an indication that Government is struggling to co-ordinate itself. Giving consumers the right incentives rather than seeking to determine what they want is a far better route.

And delivering what consumers want is key. While Liz Truss and everything she represents is currently on the political naughty step, nothing in politics lasts forever. Public support for Net Zero is not a given. Decarbonisation can only be sustainably delivered through a framework that grants us all better lives. Otherwise, people will vote for the planet to burn.