Following the Climate Change Committee’s advice on Carbon Budget 7 last week, there’s been plenty of discussion about whether Net Zero is good for growth or not.

This is, I want to emphasise, a very silly debate. If climate change happens it will have deleterious future effects, including extensive flooding, significant changes to weather systems with consequent impacts on agriculture, widespread mass migration and likely significant conflicts over water, energy, rare minerals and other resources. You might think these are already happening. While you are correct, there is considerable scope for these to get much worse.

But, importantly, these are future costs, for which we should willing to pay an amount to mitigate now. Decarbonisation, inasmuch as it brings forward a cost that would otherwise be in the future, will always have an impact on growth in the short term. The right question to ask isn’t, “Will Net Zero be bad for growth?” but rather, “How can we minimise the impact of climate policy on growth while achieving the same outcomes?”

The psychology of climate risk

The timing and extent of climate impacts are uncertain, and so therefore one’s attitude to climate policy is very much a function of one’s appetite for risk. It is no coincidence that the risk-averse populations of Europe repeatedly return leaders who emphasise action on climate change while the freewheeling Americans have elected someone who does not.

In this context, Net Zero tells you a lot more about the psychology of the UK than it does about whether it’s good for growth. It is very much a minimum risk version of climate policy. This is why the debate around it is so vituperative: you can’t rationally persuade someone to have the same attitude to risk as you, but wow do people want to try.

Confusion available on demand

Today’s exhibit is an effort to do exactly this. It’s derived from work undertaken for an investment bank. Its argument is that ‘energy availability’ is one of the key determinants of productivity and hence growth. Having worked in energy policy for 15 years I can tell you I have no idea what ‘energy availability’ is, and I’m not sure the authors of this paper do either. They say that given 2005 was the ‘peak’ year of electricity consumption then a lack of electricity available after that point is what underpins our productivity slump. The argument is given in this bullet:

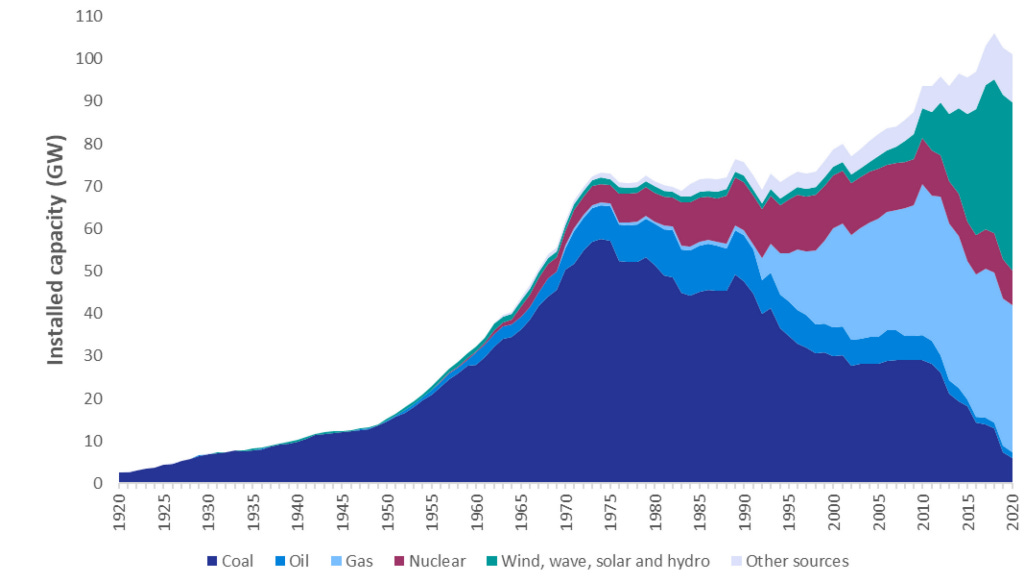

Figure 9 is this:

Observant readers will note that ‘generation’ is not capacity. In fact, the authors do not include a graph of generation capacity in their report, despite it being fundamental to their argument. I wonder why?

Generation capacity did not peak in 2005, and in fact dispatchable capacity reached its maximum in 2010. Now, it is true that energy prices started to rise in 2005, but this had nothing to do with the Climate Change Act the authors blame - which passed in 2008 - and everything to do with rising imports of gas.

When imported gas dominates your domestic supply then the marginal price of gas is set on the international market. The UK had been able to ignore the rising prices of the early 2000s but declining North Sea production meant that we became increasingly exposed to them.

In fairness to the authors, 2005 also sees the start of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS), which levied a charge of about €20/tCO2 before the price collapsed in 2007. This collapse in price did not significantly impact the overall picture of ‘energy availability’, so therefore we can conclude that the EU ETS was not the primary driver of plant closure.

Saving the Trees

What did cause the collapse in plant capacity wasn’t climate policy, but rather broader environmental policy. The EU’s Large Combustion Plant Directive obliged older coal plants to comply with limits on the production of sulphur and nitrogen oxides, amongst other pollutants, or limit their remaining running hours to 20,000 after 2007. The UK’s coal fleet being on average older and the clear direction of travel on ‘spark spreads’ versus ‘dark spreads’ led to the mass closure of coal in the early 2010s.

This ultimately did lead to higher electricity prices as the UK had no other dispatchable competition for gas, and given that gas plants had to now import fuel, our power market became dominated by the gas international price.

The trade off for this has been cleaner air and a reduction in acid rain. We have had lower growth, but we’ve had healthier lungs, more robust soils and waters that can support fish. Having border wars between English counties was never quite a risk, but this decision is very much the kind of climate debate I want to have in microcosm.

Because what we could have done rather than simply ban coal from operating without flue gas scrubbers is to tax SOx and NOx and other pollutants. Unlike with carbon, we have a very precise view of the impacts of acid rain and could price it appropriately. This indeed is what the Americans did, though rather than imposing a price they imposed a trajectory and a cap and trade scheme. This gives us the following results from this de facto policy experiment:

Rain across both the US and the EU is still acidic, but in the UK rain is now less acidic (ph 5.15) than in the Eastern USA (ph 4-4.3). Conversely, the US has grown substantially more than the UK over this period, although quite frankly acid rain schemes only form a small part of this. We opted for greater assurance of delivery against risk of reducing output.

It is this trade-off where the climate debate really should be. There are multiple pathways to Net Zero, and multiple trade-offs. My stated preference is that we take a higher risk route that relies more on letting people figure out what the right solution is than attempting to impose it from the centre. I believe that it carries the greater likelihood of maintaining a consensus on decarbonisation because it is more likely to minimise the impact on growth. But I can fully understand why someone looking at the numbers above would conclude the precise opposite.

Given that British attitudes to risk are closer than many of our continental friends to the US, the risk that we follow them down the dark path they have taken remains too high. I would hope that we can agree that this is the risk we need to manage now.

But you're missing the point: any costs imposed on the British public now - and they are huge - will make no difference at all to the global CO2 concentrations upon which climate change apparently turns. These costs are, quite literally pointless. Actually, they are worse than that, because the best chance we will have of adapting to changes in climate will be to be prosperous when it happens. If we've chosen to self-harm whilst we wait, the worse the impact will be. I just see no possible answer to this objection.

So leccy demand is going down but installed generation capacity at its highest ever!