It is not a pleasant thing, living through a period future historians may call the pre-war years. The world has a desperately fraught quality, as prior assumptions collapse and a new order - or rather a new chaos - begins to reign.

One can hardly be surprised, as a result, that the public would really rather not think about any of this. Indeed, when pressed, they would rather ensure that the least well off get to live comfortably than build a strong military.

If absolutely forced to, they would prefer to reduce overseas aid and increase taxes on business, measures which the Government has already taken. If the Government needs more cash, the public would like them to reduce spending on renewable energy.

This is of a piece with recent arguments claiming that Net Zero is not compatible with a pivot to national security. Chief amongst these is this article by Professor Sir Dieter Helm which asks us to imagine a battery operated tank stopping to recharge on the battlefield as an illustration as to why fossil fuels are vital for defence.

In this article, I’m going to argue that measures taken incidentally for decarbonisation are indeed vital for defence. And I’m going to start with tanks.

How Tanks Work

There’s an assumption in Helm’s piece that tanks having to stop to recharge during wartime would be a novel thing. But fossil fuels are not the animating spirits of vengeful Viking gods, and so existing tanks may need indeed to stop and refuel on the battlefield.

This is why, as John Pershing said, logistics wins wars. Russia’s failure to understand this point is part of the reason Kyiv did not fall in three days1.

The popular imagination had hundreds of Soviet tanks streaming through the Fulda Gap in the event the Cold War went hot, implicitly assuming that the tanks had travelled hundreds of miles to do so.

In reality from Fulda to Frankfurt is a distance of about 110km. In practice, a tank needs to be able to travel dozens of miles and fight at the end, not go on cross country jaunts. This is borne out by the actual design performance of tanks. The M1 Abrams, arguably2 the premier Main Battle Tank in the world, can travel about 250 miles on road and about 100 miles cross country. If it needs to travel further, it normally has to hop on a plane.

The M1 was designed for this specific function, and its logistics are tailored to that. Similarly, electric vehicles on the battlefield will be constrained to lighter vehicles in the near term, where electrification offers considerable advantages in endurance, noise and thermal visibility.

Low Carbon Logistics

Winning a war is therefore not simply about having a tank that doesn’t need to recharge, but rather about the capabilities needed on the battlefield and how logistical systems support their operation. Therefore the right question to ask is whether decarbonisation will improve our nation’s ability to fight a sustained war.

The first point to make is that fossil fuels are really good at being fuels. They are extremely energy dense, highly portable, and, currently, ubiquitous. The M1 Abrams is a multi-fuel vehicle that can use functionally any hydrocarbon that might be available for burning for this very purpose. In the event of a war, we would want fossil fuel availability for our military to be at its greatest extent.

Helm makes this point with reference to Labour’s ban on new fossil fuel exploration. The problem is that there is simply not that much left to explore for, and we have already passed the point at which we can be self sufficient. While fracking continues to be an option, the UK’s unhelpful geology means that it would require considerable capital investment to get underway, and is unlikely to be able to scale in time.

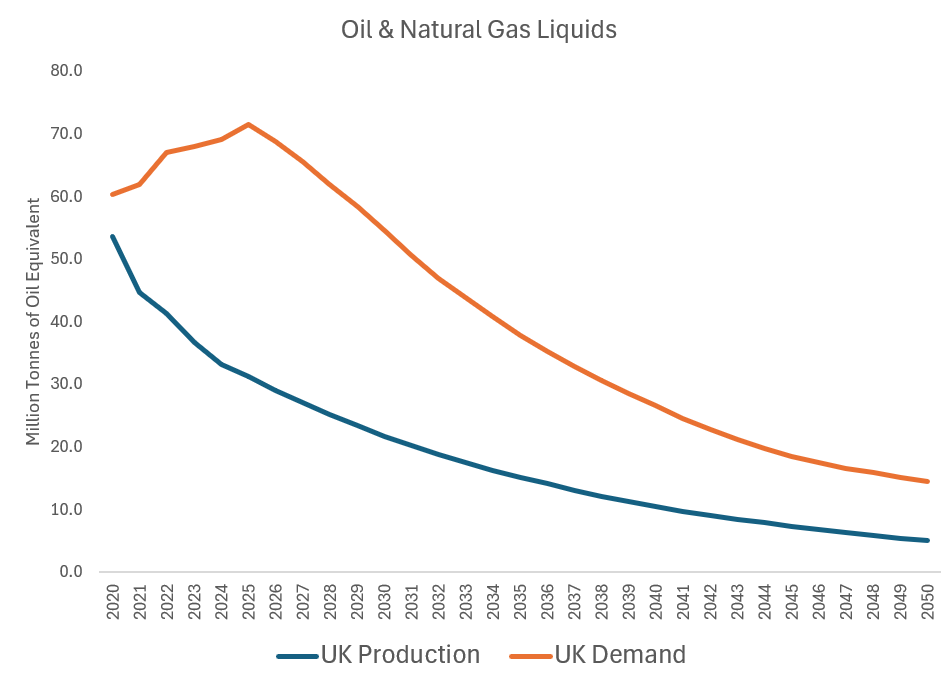

The above chart shows crude oil and NGL (propane, butane etc) output from the North Sea. The downward curve of the orange bar is projected to start next year - or rather is assumed to start next year when measures like electric vehicle rollout are intended to bite.

It should be clear that ensuring fossil fuel availability is now much more about reducing domestic demand through electrification than it is about increasing extraction. In the event of war, if we can avoid fuel rationing through fuel switching, we should be preparing to do so. In World War 2 we relied on the Americans for almost all of our oil. It should be clear that we no longer can.

However, if we create greater demand for electricity, we also need to serve that demand through indigenous production. Our natural gas import dependence is progressing even faster than our oil import dependence, so we similarly cannot rely on gas except as a backup. We have a considerable gas storage facility in the form of our National Transmission System, and we should have plans to ensure it is kept topped up in the event that the world starts to look even riskier than it does at present.

Drones, drones everywhere

Helm makes the further point that relying on indigenous production through offshore wind carries its own risks:

From a defence perspective, the North Sea is a nightmare. It presents an aggressor with a cornucopia of targets, and targets that are high value because they can lead to massive consequences if damaged and destroyed. Imagine a swarm of drones (the sort familiar in Ukraine) directed at the offshore wind farms. Each wind turbine is a small generator, so the cost of defending each relative to its value is very high. A swarm of drones only has to get some of them. Imagine an aggressor wanting to disable the British economy. Take out the Norwegian gas pipeline and there is a good chance the lights go out. Take out the electricity interconnectors in, say, January or February in line with a weather forecast for low winds, cold temperatures and dark skies; again, there is a good chance that the lights go out. Now go for the LNG terminals.

There are a numbers of errors in this analysis, starting with where the North Sea is relative to Russia and going through how drone warfare is actually progressing in Ukraine.

In order to get to the North Sea, a drone swarm would either need to fly through the Baltic, cross over the various bridges linking Denmark and Sweden before making a hard left into the North Sea, or come down via the Norwegian sea away from the coast. Either journey represents a distance of at least 2,000 kilometres. Possible, but as we’ve seen from Ukraine, typically only viable for very small numbers of drones targeted at high value facilities.

Helm’s error is to assume that the loss of any individual wind turbine is catastrophic. There will be literally thousands of wind turbines in the North Sea if the 2030 decarbonisation target is met. It takes about ten days to erect one using a single vessel, and we can run many vessels at the same time. Distributed energy generation is resilient generation.

Where Helm is correct is that the Norwegian Langeled pipeline is a strategic weakness. It is a single pipe on which much of our economy rests. We do need more LNG terminals to provide redundancy, but for security we need to get off gas. We cannot assume that in the event of a wider conflict LNG cargoes will continue to flow to us from Qatar.

The New Arsenal of Democracy

But what we really need to be secure is to be able to build things. In a war, we will need to convert existing industry to munitions factories, drone factories, and indeed weapon factories of all kinds. The problem is that we don’t have that industry. What we have is a rump manufacturing sector that successive Governments have failed to grow. Helm is not wrong to point this out, nor that steel production is vital for defence.

He is wrong to say that electric arc furnaces produce steel of a lower quality than blast or basic oxygen furnaces. The latter can produce steel from ore and therefore have historically had lower levels of impurities such as copper, which can lead to lower tensile strength. Modern production techniques can produce steel of any grade, which is why steel companies are happy to shut down more expensive alternatives. Remaining UK iron ores are of very low grade, offering little upside for indigenous refining, while we produce about 11 million tonnes of scrap steel every year, most of which we currently export. By 2030 our system is likely to be oversupplied with electricity at least 30% of the time, meaning that for a third of the year we will be able to produce steel at very low cost. Not entirely ideal for large capital investments, but ideal for stockpiling large amounts of steel at pace.

And we would need lots of steel; the Allies in WW2 used nearly 800 million tonnes of steel during the conflict. Tanks in WW2 used on average 18 tonnes of steel. The M1 Abrams weighs about 70 tonnes, much of which is composite Chobham armour composed of ceramics and… steel. Port Talbot’s new electric arc furnace will have a capacity of about 3.5 million tonnes of steel per year. We may need more.

Back to the main point, our manufacturing sector is only now regaining the peak of output it enjoyed prior to 2008. While this is in part a function of measures such as the EU ETS, it is more a function of an implicit assumption in the Treasury that globalisation can only go one way and that the UK will always have access to ‘deep and liquid’ markets for any of the products it might want. Even today, persuading officials that the UK cannot simply buy its way out of trouble through imports remains a constant activity. This has defeated multiple attempts to deliver an industrial strategy, because the Treasury doesn’t really believe in it.

“What is the additionality?” comes the call. “What does Government intervention do that the private sector will not?” These are the questions of a bygone age. The right questions are what scale of industrial capacity does the UK need to assure victory in a prolonged war, and how we should go about securing it. In the absence of the US, Britain is one of the few Western nations that can make a meaningful difference in restoring the West’s industrial might.

Time and money

The critical component of any of this is the cost of inputs into manufacturing, as they essentially represent the relative scarcity of the materials we might need to produce materiel for war. Chief amongst these is energy. Currently the UK is developing a plan to essentially rebuild its entire energy system to pivot towards lower carbon inputs. By itself this enhances resilience, but does not necessarily benefit cost.

The reason why is quite confusing. The plan linked above by the UK’s National Energy System Operator is intended to reflect the lowest cost mix of infrastructure. But because the UK operates a market in power production, this does not mean it represents the lowest price for that infrastructure. The route to that is abundant production, rather than de minimis production. The System Operator should be tasked with targeting a price in its plan, rather than a cost.

However, we cannot escape the reality that the large volumes of capital that this rebuilding of our energy system will require will itself come at a high price. There is a powerful argument that we should shove some of the costs of building a new resilient energy architecture into the longer term. We did not demand that the British taxpayer pay for the cost of World War 2 in its entirety while we were fighting it. There are some costs it is acceptable to hand off to the next generation. The cost of liberty is one, and the cost of a habitable biosphere is another. Once we have passed through this period, we can get back to building a society that does indeed ensure a fulfilling life for all.

THANKS FOR READING. OTHER THINGS YOU MIGHT LIKE:

Guy ‘Rough Beast’ Newey has launched a substack on energy at the Widening Gyre.

Sam Dumitriu has fired the starting gun on the coming debate on the Climate Change Act.

Stella Tsantekidou is holding out for an anti-hero.

Arthur Downing is continuing his personal crusade to nationalise the energy system, using underhand means like ‘facts’ and ‘history’.

The other reason is the heroism of the people of the Ukraine in the face of a brutal invading force.

AND PEOPLE WILL.

Really, really, really great piece.

One of the first things that got me to think seriously about climate tech was learning the Pentagon was one of the biggest funders of "alternative" energy, and seriously concerned with security of supply. The shale fracking thing (unfortunately in my view) blunted progress and in 2nd Bush W term a lot of that planning was shelved for the worst possible reasons.

The only thing worse than hearing that sort of ignorant sophistry from Helm was its uncritical, indeed exuberant, amplification across almost all UK media. If there's a crowd out there with funding for an anti-Tufton Street think tank that has a big chunk of its activity being in rapid response to that sort of wrongheaded nonsense, man we could use one and I'm pretty sure I know a couple fellas who'd do it well.

didn't realise Dieter Helm made that silly comment about tanks recharging. As if conventional tanks don't have to be constantly refilled by diesel and petrol!